As I read market and economic commentary, I see a split between writers who use “it” vs. “they” to refer to the Fed. Opinions can run strong about pronoun questions like this. To help you decide on the right pronoun, I ran a poll asking my readers which they prefer. I also did some additional research, which I share below.

“It” vs. “they” poll

I asked:

Do you refer to the Federal Reserve or the Federal Open Market Committee as “it” or “they”? For example, would you say “It raised rates” or “They raised rates”?

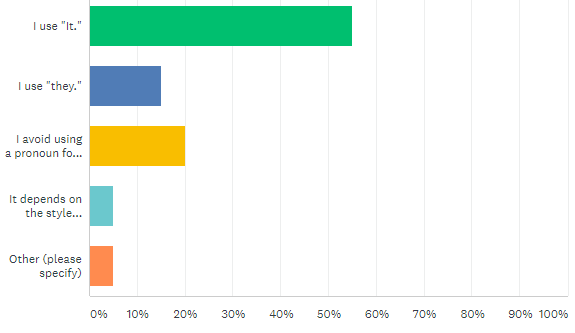

Here are the results

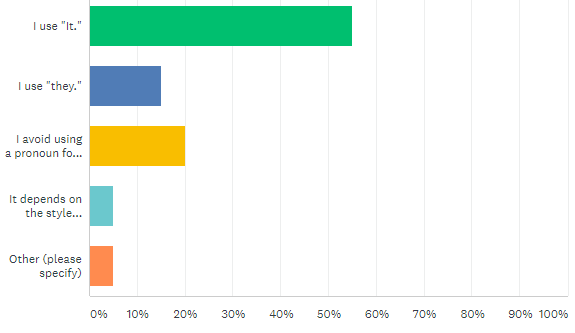

A majority (55%) of respondents use “it,” followed by 20% who avoid using a pronoun for the Fed, 15% who use “they,” and 5% who answered “other.”

A majority (55%) of respondents use “it,” followed by 20% who avoid using a pronoun for the Fed, 15% who use “they,” and 5% who answered “other.”

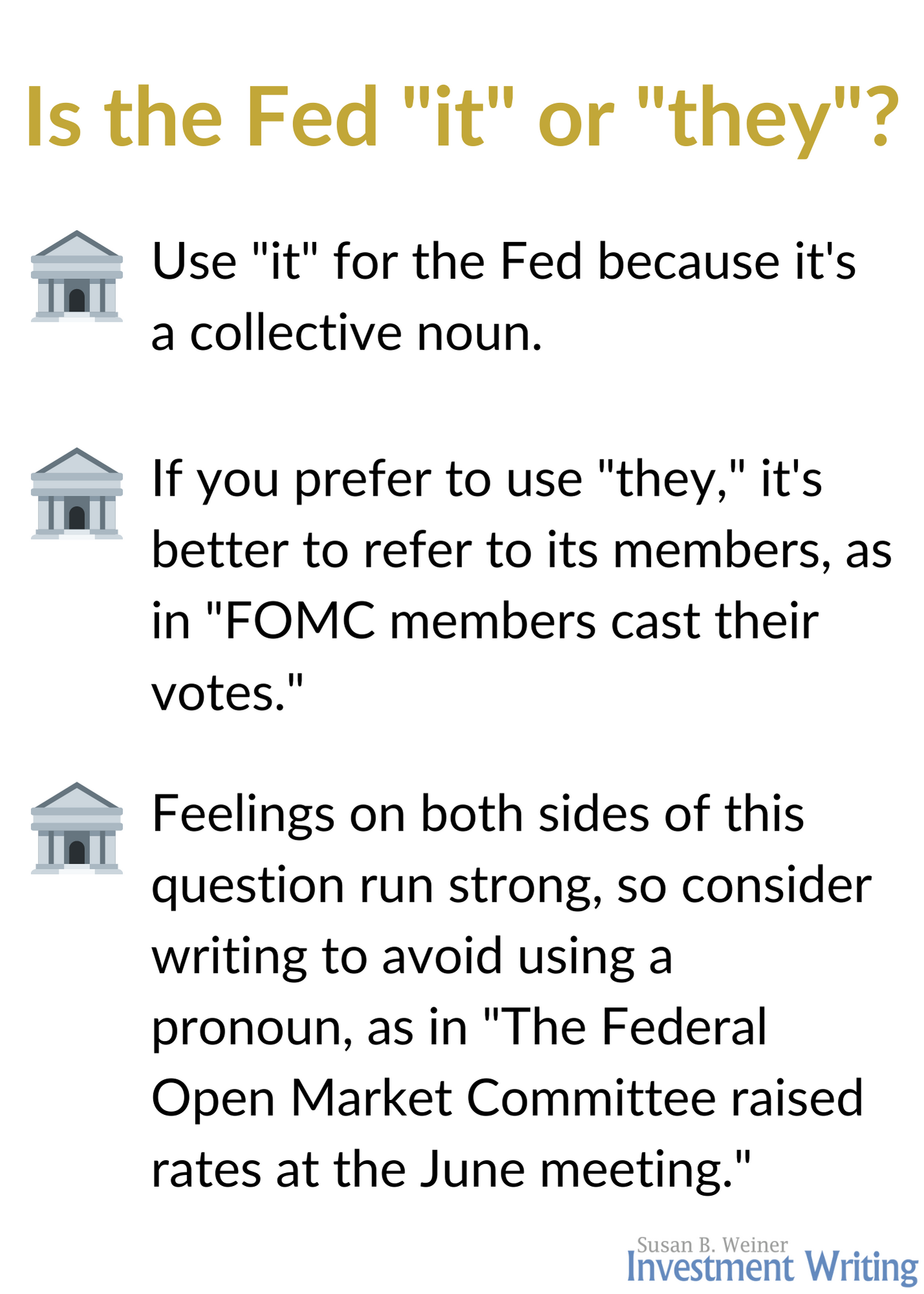

The case for “it”

Organizations are not people. That’s why I go with “it.” My readers in the “it” camp agreed. Below are some of their comments on this pronoun question (with the names of the people who commented, when they provided them):

- Corporations and government agencies and entities are referred to as it not they. It’s the law. Lol. I’m a Wall St editor. Pet peeve!

- I use “it” because I am considering them an entity and not a group of people.

- It has one voice by a single decision. Each member has their own opinion and speeches. Members are the “they” but the institution is “it.”

- I handle it the same way as I would for any institution or corporation—as an entity, not a person. And while it is made up of people, the opinions of the institution do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the individuals who work there.

- Without an ‘s’ on the end, ‘group’ is singular and is, therefore, an ‘it.’ The only exception to this that I can think of is ‘people,’ a collective and thus a plural.

- While not an expert, I’d consider the Fed to be a collective noun so singular. If it was ‘senior figures at the Fed’ or ‘Fed chiefs’ or something I’d use ‘they’, and this is what I’d be perhaps more inclined to do.—Michael Stark, AAATrade Ltd

- The Fed, like a corporate entity, seems like a singular it.—Martin Goldberg, Ph.D.

I did some research. Here’s what the Online AP Stylebook says (note the committee set “its agenda”):

The Chicago Manual of Style says, “A collective noun takes a singular pronoun if the members are treated as a unit {the audience showed its appreciation}.”

Collective nouns are treated differently in British English. From Garner’s American Usage, I know that collective nouns are typically treated as singular in American English, but as plural in British English.

The Wall Street Journal is another source that I rely on for style guidelines, as I’ve explained in “Financial jargon killer: The Wall Street Journal.” Here’s an example from “Kaplan Says Fed Should Begin Reducing Its Balance Sheet ‘Very Soon’”: “The Federal Reserve should begin shrinking its balance sheet ‘very soon,’ Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas President Robert Kaplan said Friday.”

The case for “they”

The case for “they” rests on usage and the way that people think about the entity. Many investment professionals refer to the Fed as “they” because they are thinking about the individuals who make up the FOMC. One survey respondent explained his or her preference for “they” by saying, “The Fed is a group of people.”

In “People Versus Entities,” Grammar Girl Mignon Fogarty suggests that if you want to use “they” you should refer to the people who make up the entity. Here’s her example of how to bring the people into the sentence: “Today, the MegaCo directors, who just gave themselves a raise, laid off 1,000 factory workers.”

Fogarty also says:

Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage gives a lot of credit for the growing use of plural pronouns to advertising and PR people at large corporations trying to “present a more human and less monolithic face to the public.” Nevertheless, most grammarians lean in the direction of companies being nameless, faceless entities that should be treated as singular nouns and not personified.

Style guidelines

If the organization that you’re writing for has style guidelines, check to see what it says about the Fed. Given that some investment professionals feel strongly about referring to the Fed as “they,” the company may endorse “they” over “it.”

Here’s what one respondent said:

The organization’s style guide always rules. If the organization does not have a preference for this situation, I urge them to add it to the style guide for consistency. My default is the plural pronoun.

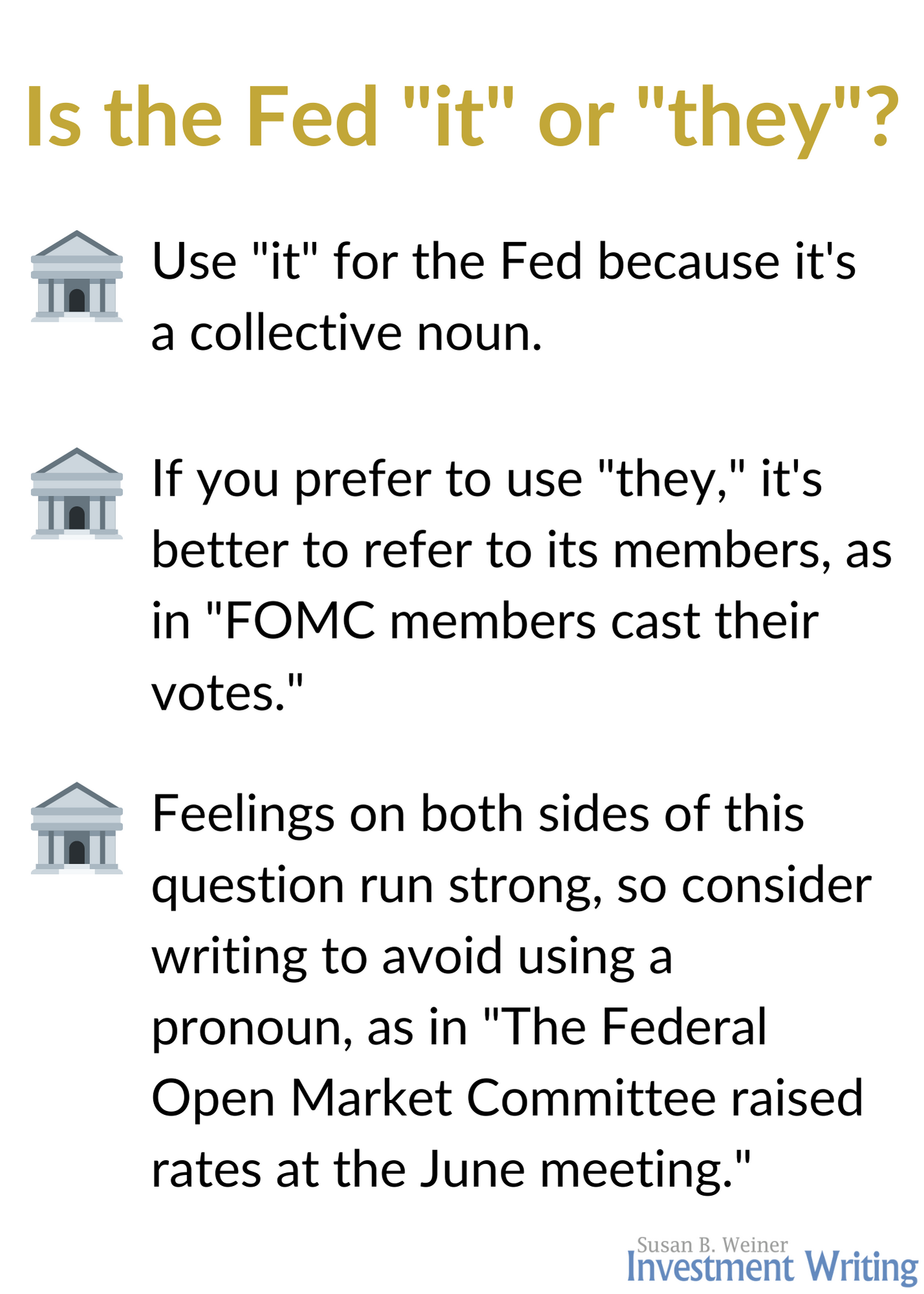

Avoiding the pronoun question

What do you do if you’re a writer or editor who works for people who can’t agree on which pronoun to use for the Fed?

Alana Garrop of Savos Investments said, “I keep the pronouns out of the conversation: ‘The Federal Open Market Committee raised rates at the June meeting.'” Notice how she avoided using “its” or “their” by referring to “the June meeting.”

This is a great workaround when choosing “it” or “they” means you’re going to offend someone. It reminds me of the workaround to avoid deciding on “Treasuries” vs. “Treasurys.”

Note: I’ve updated this post, which originally ran in December 2017.

A majority (55%) of respondents use “it,” followed by 20% who avoid using a pronoun for the Fed, 15% who use “they,” and 5% who answered “other.”

A majority (55%) of respondents use “it,” followed by 20% who avoid using a pronoun for the Fed, 15% who use “they,” and 5% who answered “other.”