Abbreviation: U.S. or US for United States?

A client used to abbreviate the United States as U.S. and the United Kingdom as UK. The inconsistency drove me batty. I couldn’t find a reason for that disparity. But it made me wonder, what are the rules for how one should abbreviate the United States?

What style guides say

The online AP Stylebook says “Uses periods in the abbreviation.” However, “In headlines, it’s US (no periods).” AP style seems to allow for multiple space-saving adaptations for headlines—like using numerals in headlines, but spelling out numbers under 10 in the body of the text. By the way, AP style has a similar rule for abbreviating United Kingdom.

Garner’s Modern American Usage says of U.S. and U.S.A.,

As the shortened forms for United States of America, these terms retain their periods, despite the modern trend to drop the periods in most initialisms… U.S. is best reserved for use as an adjective…, although to use it as a noun in headlines is common. In abbreviations incorporating U.S., the periods are typically dropped <USPS> <USO> <USNA>.

However, other style guides favor US. For example, the MLA Style Center says,

In its publications, the MLA uses the abbreviation US. (Practices among publishers vary, however, and it is not incorrect to use U.S. Whichever abbreviation you choose, be consistent.)

The MLA prefers to spell out the name United States in the main text of a work, in both adjective and noun forms. It uses the adjective form sparingly.

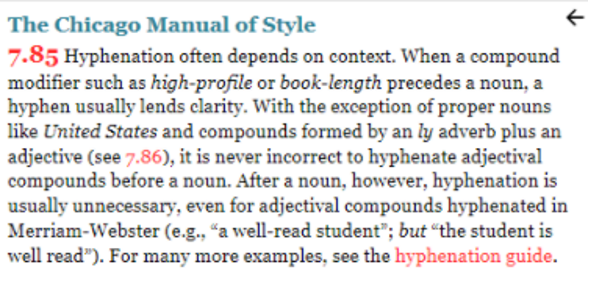

The Chicago Manual of Style also favors US, as it says in an online FAQ.

Until the 17th edition, Chicago style was to spell out the noun in running text, but abbreviate the adjective as US. Now, we allow US as a noun, but only if the meaning is clear from context—that is, the usage is subject to editorial discretion.

What you should do

Notice how the MLA Style Center mentions consistency? Consistency is key because it makes your publications easier to read. Your organization should pick one style and stick with it.

I am sticking with U.S., unless I write for a publication with a style guide that calls for US. What about you?

If you like this post, you may also like “How to capitalize financial acronyms.”

U.S. vs. UK

I couldn’t find any rules suggesting why one should use U.S. for the United States along with UK for the United Kingdom. Do any of you have ideas about this? Please let me know. Curiosity is killing me.

One of my friends suggested that some publications mix the two styles of punctuation because UK is preferred in the United Kingdom.

Another suggested that it’s OK to drop the periods from UK but not U.S. because uk is not a real word, while us is a widely used pronoun.

NOTE: I expanded this blog post on Oct. 31, 2022.