FEB. NEWSLETTER: Format your numbers correctly

Formatting ordinal numbers

It drives me crazy to see formatting like “10th” in people’s writing. I believe it happens because Microsoft wrongly makes superscript its default for ordinal numbers. But that’s wrong, at least according to Associated Press style, which shows the “th” suffix in regular font. I couldn’t find any well-known style guide that suggests using superscript with ordinal numbers. The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) generally spells out ordinal numbers, although it makes exceptions for informal communications. However, CMOS never superscripts ordinal suffixes.

You can “Turn off superscripting of ordinal numbers in Word.” Doing this removed a big source of irritation from my life.

On a related topic, see my post on “How to write calendar dates in your financial communications.”

Is it OK to send cold emails?

A cold email is “an unsolicited e-mail that is sent to a receiver without prior contact,” as defined by Wikipedia.

Yes, it’s OK to send a cold email, but you should act within the bounds of laws governing email communications in the region you’re targeting. For more information, see “Is Cold Email Legal? Best Practices for Compliance” from Hunter.io, a website that helps people find and verify email addresses.

Could your older clients benefit from mentoring younger people?

Individuals who are age 60 or older might enjoy providing online intergenerational mentoring as facilitated by Eldera. According to the website, opportunities are open to individuals who:

- Have six (or more!) decades of life experience

- Have an internet connected device that can access Zoom

- Can pass a background check

- Possess kindness, generosity, and curiosity

I learned about this service in The Boston Globe’s “How do you define old? A push to mine wisdom, ease isolation among young and old.”

Bilingual language podcasts

I’ve been studying Spanish and reviewing Japanese using Duolingo since before the pandemic hit. But I only recently started listening to Duolingo’s Spanish-English podcasts, which tell interesting stories in a combination of intermediate Spanish with enough English to get me through the bits I don’t understand. The stories would interest me even if they were only in English. For example, there’s a story about how the family of one of Duolingo’s founders dealt with a relative getting kidnapped for ransom.

Duolingo offers bilingual podcasts for English-speaking students of Spanish and French and for Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking students of English. I wish Duolingo would add a bilingual Japanese podcast.

Recycle office equipment and supplies

Staples recycles a lot of office supplies and equipment, as well as school supplies. Probably more than you think. For example, it recently added single-use batteries to the list of items it recycles. It will recycle monitors for a fee. I was surprised to learn Staples recycles earbuds, pencils, and computer mice.

Lemon crinkle cookies

I discovered this recipe for lemon crinkle cookies when I needed to prepare for a cookie swap. The recipe is from King Arthur Flour, which is a reliable source of recipes for baked goods.

When I needed to adapt the recipe to yield 24 cookies instead of 22 to meet the cookie swap requirements, I found a solution by calling the website’s Baker’s Hotline.

This recipe made me the winner of the cookie swap competition.

What my clients say about me

“Fast, effective, insightful. I can think of no better resource for superior financial writing.”

“Fast, effective, insightful. I can think of no better resource for superior financial writing.”

“Susan has an exceptional ability to tailor investment communications to the sophistication level of any audience. She has an uncanny ability to make very complex investment and/or economic topics accessible and understandable to anyone.”

“Susan’s particularly good at working through highly technical material very quickly. That’s very important in this business. A lot of people are good writers, but they have an extensive learning curve for something they’re unfamiliar with. Susan was able to jump very quickly into technical material.”

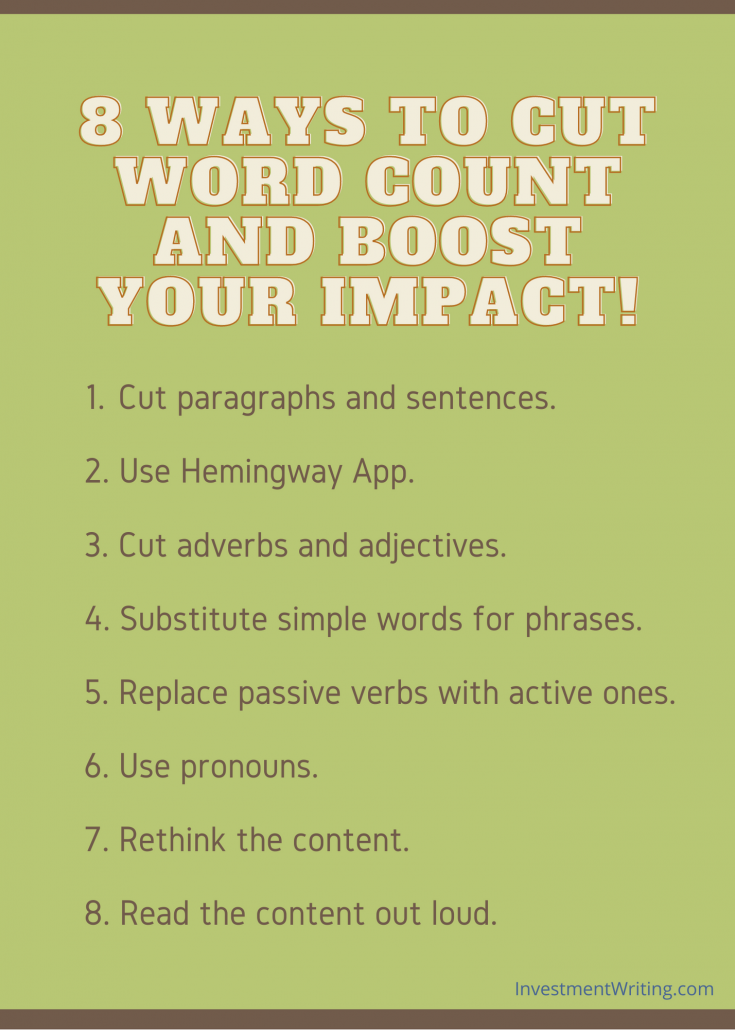

Improve your investment commentary

Attract more clients, prospects, and referral sources by improving your investment commentary with 44 pages of the best tips from the InvestmentWriting.com blog.

Tips include how to organize your thoughts, edit for the “big picture,” edit line by line, and get more mileage out of your commentary.

Available in PDF format for only $9.99. Email me to buy it now!

Boost your blogging now!

Financial Blogging: How to Write Powerful Posts That Attract Clients is available for purchase as a PDF ($39) or a paperback ($49, affiliate link).