6 tips to keep your compliance officers happy

How can I work with my firm’s compliance officers?

That was the most frequent question I heard when I spoke on “How to Write Investment Commentary People Will Read” to the CFA Society Atlanta earlier this year. At the time, I could only answer verbally and suggest that the questioners flip the perspective of my post on “7 ways Compliance can work with investment writers for their mutual success.” That’s why, in this post, I focus on how marketers and advisors can build constructive working relationships with the compliance professionals at their firms.

I’ll focus on investment marketing compliance in this post. However, if you’re a financial advisor, you can tweak my suggestions to fit your situation.

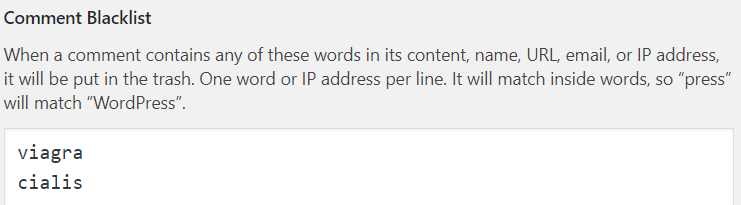

1. Create a compliance checklist

Checklists are a great tool for the writing process, as I’ve discussed in “5 proofreading tips for quarterly investment reports,” “Investment commentary numbers: How to get them right,” and Financial Blogging, which includes several checklists. They help with compliance requirements, too.

If you’ve been submitting pieces for compliance approval for a while, you probably have an idea of what triggers a negative reaction. For example:

- Promissory language—I know you won’t guarantee results, but compliance officers are sensitive to gradations of language. List examples of what sets them off, as well as the language that they offer as solutions. Here are some examples provided by financial writer Susan Trammell: (red flag) The fund enables you to invest in high-quality convertibles vs. the fund offers the opportunity to invest in high-quality convertibles; (red flag) growth stocks have routinely outperformed value stocks over the past decade vs. growth stocks have historically outperformed value stocks over the past decade; (red flag) robo investing will transform the investment landscape vs. robo investing is likely to transform the investment landscape; (red flag) populist sentiment will hammer the FANG stocks vs. populist sentiment could put the brakes on high-flying social media companies.

- Mentions of specific investments, especially specific products, and their performance—You may wish to avoid mentioning specific investments unless absolutely necessary. These topics typically require disclosures. Especially for mutual funds, the disclosures can be long and require quarterly updating. Instead, as Susan Trammell suggests, “find a way to help your audience understand your meaning without mentioning brands. For example, you might refer to the leading smartphone innovators, the largest online retailers, cash-strapped clean energy car manufacturers, or pioneering ride-hailing companies. Your readers will figure it out.”

- Cherry-picking—For example, compliance doesn’t want you to discuss only your stock picks that are doing well, or to vary the periods of performance (or the benchmarks) in your quarterly performance tables to show only those that are favorable to your firm’s performance. Familiarity with the CFA Institute’s Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS®) can help you to get compliance on your side. (The CFA Institute offers an annual educational GIPS conference. The 2019 GIPS conference will be held Sept. 11–12 in Scottsdale, Arizona.)

- Testimonials—These are forbidden to investment professionals who are regulated by the SEC. Susan Trammell suggests some workarounds, saying “You might point out that most of your new customers come from client referrals, that you have many second- and even third-generation investors, or that the average tenure of your client relationship is so many years. Just be honest with your stats, and be sure to have the data to support them!”

On the positive side, you can list the rules and language that satisfy compliance requirements. For example:

- Nonpromissory language—Sometimes referred to as “weasel words” because they sap the strength of your statements, these phrases are necessary to avoid misleading clients. They include phrases such as “we believe,” “I think,” “it appears,” and “historically” (in phrases such as “Historically, small-cap stocks have outperformed large-cap stocks over the long run”).

- Disclosures—Some boilerplate disclosures can be used as is, regardless of when your writing is distributed. Others, such as assets under management and performance, must be updated quarterly. You may find it useful to keep the text for unchanging disclosures in your checklist so you can simply copy-paste it. For more complex, changeable disclosures, make a note of the source you’ll contact for current information. As a complement to your checklist, you can save fixed disclosures and placeholders for period-specific data elements in your document templates.

- Documentation—Develop a sense of the kind of facts for which you’ll need to provide backup. You may need to footnote the information. Or, it may be enough to have the source documented in case the regulators have questions. In my days on the staff of a large asset manager, I filled file cabinets with documentation. I imagine that most of this information is saved electronically these days. Make sure you know how to retrieve the information.

- Information that helps you be accurate—As I discussed in “Investment commentary numbers: How to get them right,” when you’re not accurate, you undermine your credibility, embarrass yourself, and upset your compliance department. Your compliance officers appreciate accuracy.

Your checklist can note the guidelines for proper sourcing of exhibits. You can also remind yourself to check that you’re referring to the current quarter in your commentary. This is especially important if you start your draft by updating the previous quarter’s commentary. On a related note, observe your firm’s style guidelines—if they exist—(or create your own style guidelines).

In addition to helping you with compliance, a checklist can ease your workload. For example, if you’re a busy portfolio manager, you can ask your assistant to review your draft against the checklist. Even if you’re working alone, it’s less taxing to check a list than to try to recall the important guidelines on your own. Checklists lessen the load on your brain.

A good way to expand your list—and help your colleagues—is to ask them for their input. They may know nuances that you don’t. In addition, by sharing your checklist with them, you may save them from mistakes that will slow compliance approval of their writing.

2. Meet with a compliance officer

One way to build a partnership with your compliance officer is to schedule a meeting to discuss guidelines for the kind of pieces that you write most regularly. Do this when there is no pressing deadline or quarter-end crunch in the way. I think they’ll be willing to spend this quality time with you. Your compliance officer wants you to succeed at your job. After all, your marketing and client retention efforts help to pay their salary.

What can you discuss with them? If you’ve completed your compliance checklist, you can share it with the compliance officer (consider sending it in advance). You can tell them the rules and guidelines you seek to follow and ask them if there are others they want to include.

Learn how your compliance officers want to work with you. For example, do they prefer to see a first draft in some cases, but the final draft in others? It’s also important to ask what kind of lead time compliance needs to review your writing. In addition, are there steps you can take to make it easier to review your work and to speed up review when necessary? You can also ask them about my suggestion #3.

A colleague says:

I’m a huge proponent of building a relationship with compliance. Depending on how the firm is set up, compliance officers generally interpret the law and consult with the firm’s attorneys. Compliance officers who trust and respect you can act as an advocate. Treat them poorly and see what happens. They hold all the cards.

The same colleague suggests that you meet first with compliance, and then compile your checklist. I can see how that might be ideal. However, access to compliance isn’t always easy, especially if you’re a junior employee. There’s a lot that you can figure out on your own, especially as you see how compliance responds to your content.

3. Ask for training in marketing compliance

If you work for a large firm, your employer may have training available for you, possibly as part of its ethics training. When I was an “access person” as a contractor for a large U.S. investment manager, I had to take annual computerized training that touched on marketing topics.

If your firm lacks a prepared training program, you can still ask your compliance officer to gather the relevant employees for a discussion of compliance. Alternatively, you can suggest hiring an industry compliance consultant to come on-site to conduct a marketing compliance training session. Some can even use your firm’s own materials in their presentation, as NRS did for a colleague. It will probably help if you identify your topics of interest in advance. Your firm’s compliance professional will probably have ideas of their own.

Perhaps the trainer can show a before-and-after version of a marketing piece, explaining why changes were made to satisfy compliance. In my earlier post on marketing compliance, I suggested that compliance officers create a three-column table consisting of

- Example

- What’s wrong with the example—and why

- A rewritten example that works—and why

While this might be too much for a PowerPoint slide, it could be great as a reference guide that reinforces in-person training.

4. Identify useful resources

You probably don’t want to read SEC documents. However, compliance experts’ interpretations of the regulators’ words can be more useful. Some compliance consultants have newsletters and blogs that may touch on marketing issues. When you google a topic, you’ll often find reputable firms offering understandable articles on rules and regulations.

5. Treat compliance with respect

Try to work within the process that compliance prefers. If you treat compliance preferences respectfully, you’re more likely to receive cooperation when you’re in a rush or need to push back on a suggestion from a compliance professional.

Respect involves being mindful of the demands on the time of compliance professionals. As a colleague says, “They typically have dozens of items to review, so anything you can do to make it easier on them would be appreciated.” This colleague suggests, for example,

Once you get guidance on a piece, share it with your colleagues so that they can incorporate it in their own work. This saves the compliance reviewer from having to make the same comments on pieces coming from different people, and it makes the writers more efficient at the same time.

For my part, I suggest that you don’t ask for rush processing if it’s not necessary.

By the way, if you’re an investment professional or advisor feeling annoyed by compliance, a colleague says that you should remember that your “licenses and livelihoods are at stake.” The stakes are high.

6. Don’t fear compliance

Respecting compliance doesn’t mean that you should fear it.

For example, although respect is important, it doesn’t mean that you never question changes made by compliance. In my experience, sometimes compliance makes changes to improve style, rather than to improve the text’s compliance. Sometimes those are great stylistic improvements. When they’re not, you can ask, “Is this a style recommendation, not a change that’s required for compliance?”

A colleague agrees that you can negotiate changes with your firm’s compliance professionals, saying:

They normally are open to other wording. Changes they suggest may be the first or safest thing that comes to mind, but not necessarily the final answer. Work something out over the phone, not always by email. Compliance understands that you’re trying to market yourself or company and they normally want to help you do so, but in a compliant way.

That’s a good point about getting on the phone instead of relying on an email, in which nuances can be lost. It’s easier to discuss several alternatives in a live conversation. Also, a phone call may cut through the clutter in the compliance professional’s inbox. When I held a staff job, I’d sometimes walk to the compliance head’s office to make my questions harder to ignore. However, again, use this kind of “ambush” tactic with moderation. Being respectful, and even friendly, can go a long way to improve your relationship with compliance professionals.

Also, you can use the information in “Ammo for your plain-language battle with compliance” to battle against a compliance officer who prefers clunky formal language.

Another colleague urges writers to take a positive attitude toward compliance, saying:

I’ve once again been informed that “our compliance department is the most conservative in the industry”—it’s almost comical. Over and over again, I meet marketers and sales teams who believe that the securities laws are antiquated and that compliance is trying to keep them from being successful. The approach often taken is “we’ll hide it from them until the last minute and then they’ll have to approve it, or maybe we’ll get lucky since ‘they’ all say different things.”

I agree that you shouldn’t wait until the last minute to consult compliance. The results could derail your marketing.

Keep on learning!

As you evolve as a writer, you’re likely to encounter new challenges—and successes—in writing within the confines of compliance constraints. Keep on learning and documenting your lessons in your checklist.

As you learn more, you may wish to break one checklist into multiple lists to prevent it from becoming unwieldy. For example, you might create a specialized checklist for a specific kind of document.

Speaking of learning, I’d like to thank the colleagues who gave me feedback on this blog post. As I expected, they prefer anonymity, which I suspect is partly to keep them in the clear on compliance rules and rules about speaking on the record.