Do you get tired of generating original material for your blog? Do you attend talks on topics that would interest your blog’s audience? If so, you can benefit from this template for blogging (or writing an article) about a talk. This blog post template will help you to spend less time thinking and writing. Plus, you’ll get better results from what you write.

This blog post template draws on my many years of blogging about presentations that I attended at the Boston Security Analysts Society. Plus, I also covered conference presentations as a staff reporter for Dalbar’s Mutual Fund Market News (now Money Management Executive) and as a freelance writer for Advisor Perspectives. If you’d like to learn more about writing blog posts, check out my financial blogging class.

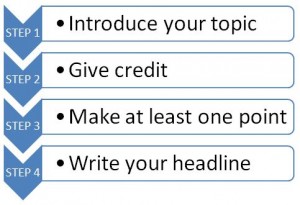

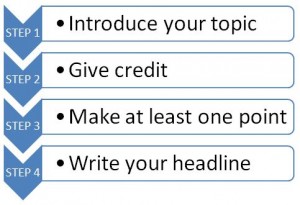

Here is the process you can follow to apply my blog post template:

- Introduce your topic

- Give credit

- Make at least one point

- Write your headline

Step 1. Introduce your topic

Don’t make the mistake that too many amateurs do. Don’t kick off your article by saying “I went to a talk and it was great.”

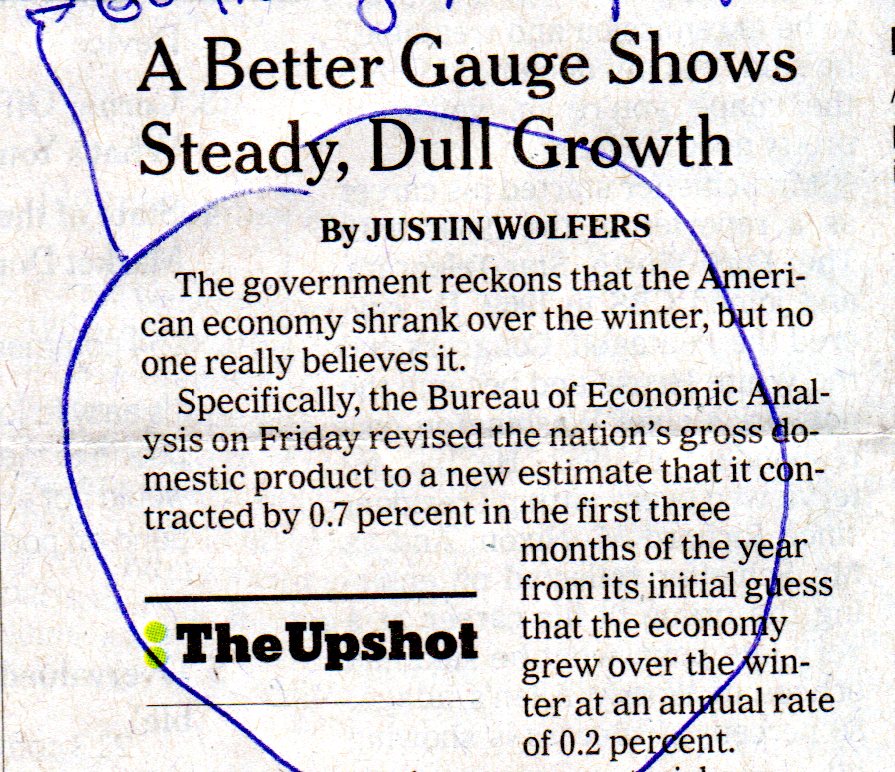

Instead, start by sharing the speaker’s topic or main point. For example, I led with “‘U.S. economic growth is recovering robustly, receiving the usual cyclical boost from housing and inventories,’ said Dean Maki” in “Recovery will be stronger than consensus, says Barclays Capital chief U.S. economist,” a 2009 blog post. This quickly told the reader what they’d learn in the piece.

Doesn’t that beat the heck out of an introduction that lacks substance? For example, I can imagine an inexperienced writer starting with something like the following: “I went to one of the Boston Security Analysts Society’s excellent lunch presentations for Boston area investment professionals where Dean Maki, managing director and chief U.S. economist of Barclays Capital spoke and I got some great insights into the U.S. economy.” Yes, I’m exaggerating how badly most people write. However, I bet that you’ve read plenty of blog posts and newsletter articles that started similarly. Still, I am grateful that those authors take the time to credit the source of the observations that follow their introductions. That’s far better than presenting someone else’s ideas as your own.

Step 2. Give credit

If you pick up some great ideas at a talk, it’s good to give credit to your source. Just don’t write it in the way that I’ve parodied in the preceding paragraph.

Name the speaker, the title of his or her presentation, the sponsoring organization, and the date, if applicable. This information helps your readers to assess the credibility of the information in your blog post. The date will cue in the reader if information cited in the presentation is no longer current.

Here’s how I gave credit in the first paragraph of the Maki post:

“U.S. economic growth is recovering robustly, receiving the usual cyclical boost from housing and inventories,” said Dean Maki, managing director and chief U.S. economist of Barclays Capital in his “U.S. Economic Outlook” presentation to the Boston Security Analysts Society (BSAS) on December 8.

In the Maki post, I covered steps 1 and 2 in my first paragraph. Then, I moved to Step 3.

Step 3. Make at least one point

When you report on a talk, you don’t need to cover everything the speaker says. Especially in a short blog post, it’s fine to focus on one point.

In the Maki post, I focused on the economy’s strength, the theme introduced in my first paragraph.

Here’s the structure for the rest of the post, in terms of points made:

- Paragraph 2: Maki sees a strong recovery, in contrast with the consensus, because he doesn’t see tight credit as a problem.

- Paragraph 3: He thinks strong growth will be driven by these factors.

- Paragraph 4: Here are his specific predictions for the economy.

- Paragraph 5: Maki sees two things that could derail his predictions.

Here’s the flow of the piece, in terms of the actions I took:

- State the speaker’s main opinion.

- Provide supporting evidence.

- Go into more detail about what the information covered above means.

- Provide information about what could go wrong.

Here’s a generic version of my blog post template for you to follow.

- State the speaker’s main opinion.

- Make your first point. For example, you could describe the main piece of supporting evidence offered by the speaker. Or, you could describe the first of the speaker’s three main suggestions. Or, tell a story that illuminates the speaker’s main opinion.

- Make your second point. For example, you could explain the second piece of supporting evidence offered by the speaker. Or you could explain why you disagree with the speaker’s main point.

- Make your third point. For example, you could introduce a related theme discussed by the speaker.

- Offer a conclusion or call to action. For example, if you’re an investment or wealth manager reporting on economic predictions, you might say how the predictions will influence how you manage money for your clients—or how the predictions should influence your readers’ behavior.

Step 4. Write your headline

It’s often easier to write your headline after you’ve completed writing your entire blog post or article. Writing may help you to identify your main point so you can feature it in your title. For the Maki post, I chose “Recovery will be stronger than consensus, says Barclays Capital chief U.S. economist.”

In addition to highlighting the main point, I included Maki’s corporate affiliation. I chose that over his name because I figured that Barclays Capital had better name recognition.

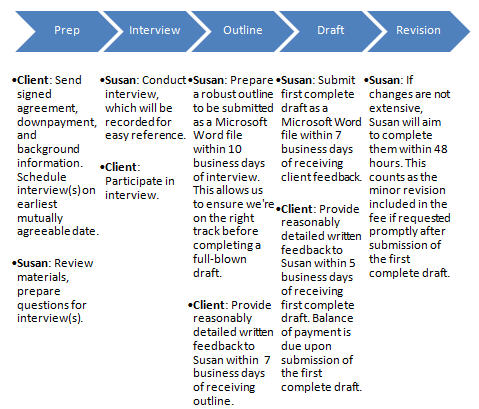

Apply this blog post template to a longer article

When you write a longer article, you may feel tempted to cover more of the speaker’s twists and tangents. You may also try to present the information in the order and structure used by the speaker. Sticking closely to the speaker’s approach may hurt your article or blog post.

Some speakers wander all over the place. That’s fine when you’re listening to an insightful, entertaining speaker. However, that structure doesn’t translate well into writing. I urge you to pick one theme and stick with it.

I ran into the problem of the wandering speaker when I wrote “Dan Fuss: The 50-Year Opportunity in Bonds” for Advisor Perspectives in Dec. 2008. Fuss held his audience rapt, but he rambled. He’s a leading thinker in the area of fixed income, so any speech by him is an opportunity to gain valuable insights. Still, his talk didn’t lend itself easily to becoming an article. However, along the way he made one point that riveted me: Opportunities in the bond market are as attractive now as they have been in at least 50 years.

The 50-year opportunity in bonds became the focus of my piece, which hit the top 10 list on Advisor Perspectives. I focused the article under two headings. First, “Treasuries overvalued, and investment-grade and high-yield attractive”; and second,”When will it end?”

Believe me, the talk Fuss gave was not as focused as my article. It’s fine for a talk by a leading thinker in the field to ramble. It’s not okay for a written piece. To fix the problem, I created a structure that didn’t exist in the original talk.

To identify the main themes for my article, I used mind mapping, which I teach in my book and my financial blogging class. Then, I used the mind map to organize my thoughts before writing the article.

Sometimes the most important decision you make in writing up a speech is what to omit. I ignored lots of my notes because they didn’t support my theme of the 50-year opportunity in bonds.

Try this blog post template

If you use my blog post template to write about a talk that you attend, please post a link in the Comments section of this blog. If you’d like more guidance from me on how to write this kind of piece, you can sign up for one-on-one coaching or my financial blogging class.

If your white paper doesn’t identify a problem experienced by your target audience, then it’s not going to attract prospects or convince referral sources to pass along your name. You need to answer the question of “

If your white paper doesn’t identify a problem experienced by your target audience, then it’s not going to attract prospects or convince referral sources to pass along your name. You need to answer the question of “ Grant’s interest in procrastination was inspired by one of his graduate students. “She told me that her most original ideas came to her after she procrastinated,” says Grant. He and his student tested whether her experience applied more broadly. Their experiments suggested that “procrastination encouraged divergent thinking.” Why? Because it gives us a chance to move beyond “our first ideas, which are usually our most conventional.”

Grant’s interest in procrastination was inspired by one of his graduate students. “She told me that her most original ideas came to her after she procrastinated,” says Grant. He and his student tested whether her experience applied more broadly. Their experiments suggested that “procrastination encouraged divergent thinking.” Why? Because it gives us a chance to move beyond “our first ideas, which are usually our most conventional.”