MARCH NEWSLETTER: Curly versus straight

What kind of quotation marks do you use in your writing?

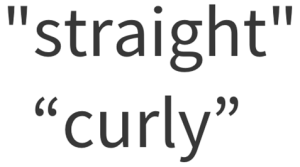

Did you know that there are two kinds of quotation marks—straight and curly? Straight quotation marks don’t curve, whereas curly quotes seem to wriggle on the page (see image below). The actual appearance of the marks will vary depending on the font you use.

Straight quotes are a hangover from the days of typewriters when you would have needed separate keys to show the curly quotation marks that appear on the left versus those that appear on the right. Today, software can automatically supply the appropriate quotation marks. In fact, curly quotes are also known as “smart quotes” because they’re smart enough to lean in the appropriate direction.

Straight quotes are a hangover from the days of typewriters when you would have needed separate keys to show the curly quotation marks that appear on the left versus those that appear on the right. Today, software can automatically supply the appropriate quotation marks. In fact, curly quotes are also known as “smart quotes” because they’re smart enough to lean in the appropriate direction.

Here’s what one blog says about straight versus curly in “Curly quotes and straight quotes: a quick guide.”

Straight quotes come from typewriter habits. Typewriter character sets were limited by mechanics, so they were replaced with straight quotes. That’s not an issue anymore with word processors and modern typing. Straight quotes are no longer a necessity.

Curly quotes are typically preferred by writers today because they’re more legible and flow better with the content. Straight quotes rarely have a place in any type of modern writing or typography, the technique, and art of arranging type. Designers and people who work with typography tend to stay away from straight quotes as a rule of thumb.

I favor curly quotes because they’re more modern and are generally preferred by my clients. If your company prefers straight quotes, that’s OK, but please use that style consistently. It’s jarring for some readers if you switch between styles.

There are some rare cases in which straight quotes might be preferred. “The ‘Smart Quote’ Struggle” discusses how the use of curly quotes is not supported for searches in some scholarly literature databases. (Thanks, Robyn Bradley, for this link!) This is also true, according to my techie husband, when technical query text is pasted from word processors directly into most database management software that uses some form of structured querying language (SQL).

To turn curly quotes on or off in Microsoft Word or PowerPoint, read “Smart quotes in Word and PowerPoint.”

Historic versus historical

Do you know when to use “historic” instead of “historical” in your financial writing?

For example, if you’re talking about the market setting new highs, you might refer to “historic highs.” That’s because “Historic is most commonly used for something famous or important in history,” as explained in “What’s the difference between ‘historic’ and ‘historical’?” on the Merriam-Webster website.

Treasuries or Treasurys?

How do you write the plural of “Treasury”? Read my take on the topic in “Treasurys vs. Treasuries — Which is the right spelling?”

Learn more about hospice care and the end of life

I wish I had known more about hospice care and the process of dying before a family member started it some years ago. Nothing to Fear: Demystifying Death to Live More Fully is a practical, down-to-earth book written by hospice nurse Julie McFadden. McFadden has a YouTube channel where you can get a taste of her approach to this topic.

On this topic, a friend also recommends The Good Death: A Guide for Supporting Your Loved One through the End of Life by nurse Suzanne B. O’Brien. The book is scheduled for release on March 18, 2025.

Flemish art at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem

I’m a big fan of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts.

The museum is currently hosting a traveling exhibition of Flemish art, “Saints, Sinners, Lovers, and Fools: 300 Years of Flemish Masterworks.” The show runs through May 4, 2025.

What my clients say about me

“Fast, effective, insightful. I can think of no better resource for superior financial writing.”

“Fast, effective, insightful. I can think of no better resource for superior financial writing.”

“Susan has an exceptional ability to tailor investment communications to the sophistication level of any audience. She has an uncanny ability to make very complex investment and/or economic topics accessible and understandable to anyone.”

“Susan’s particularly good at working through highly technical material very quickly. That’s very important in this business. A lot of people are good writers, but they have an extensive learning curve for something they’re unfamiliar with. Susan was able to jump very quickly into technical material.”

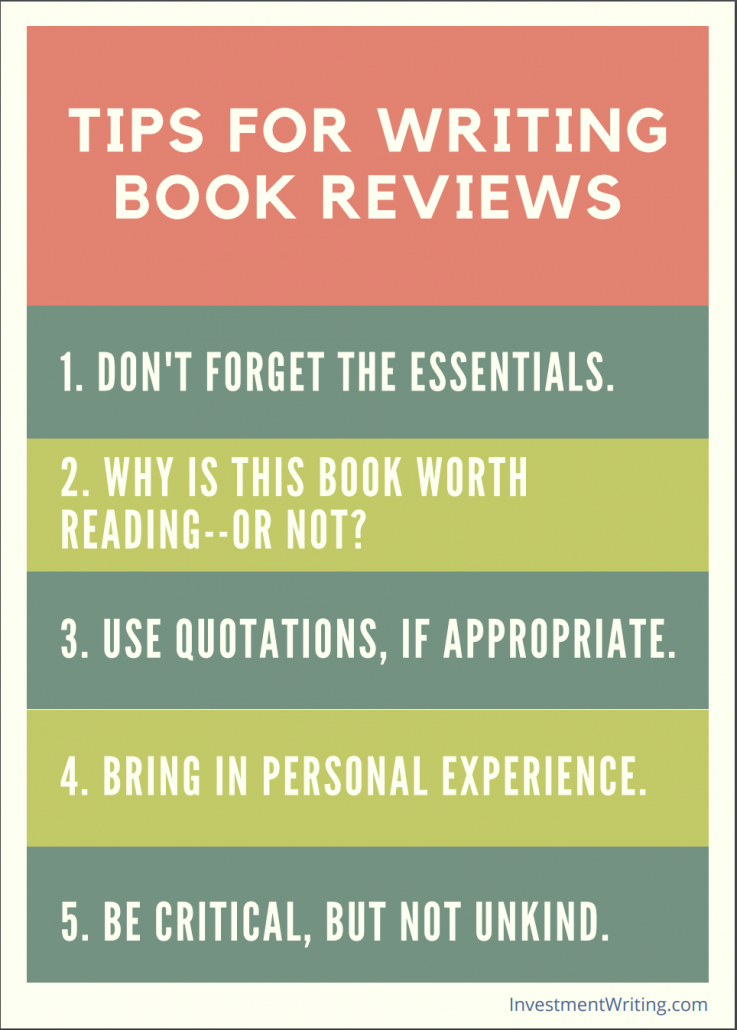

Improve your investment commentary

Attract more clients, prospects, and referral sources by improving your investment commentary with 44 pages of the best tips from the InvestmentWriting.com blog.

Tips include how to organize your thoughts, edit for the “big picture,” edit line by line, and get more mileage out of your commentary.

Available in PDF format for only $9.99. Email me to buy it now!

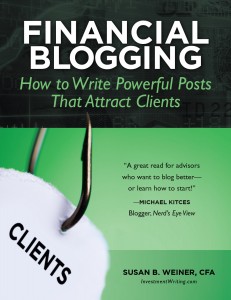

Boost your blogging now!

Financial Blogging: How to Write Powerful Posts That Attract Clients is available for purchase as a PDF ($39) or a paperback ($49, affiliate link).