“In order to” versus “to”

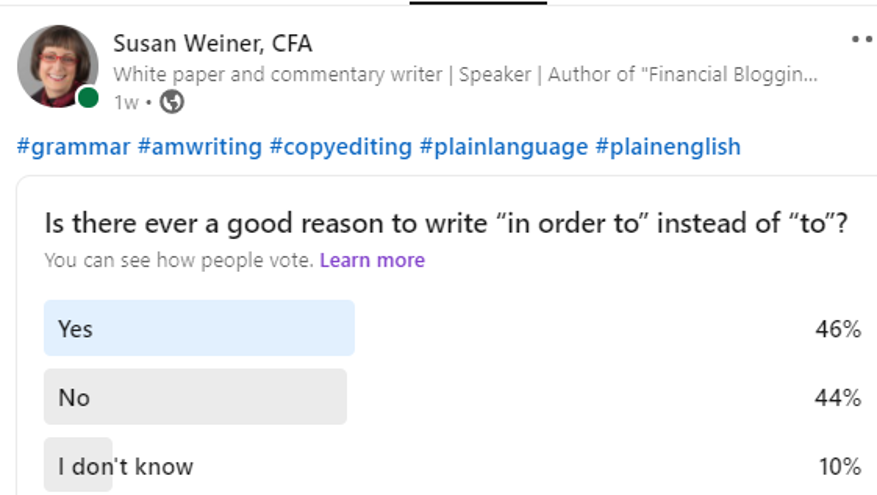

Is there ever a good reason to write “in order to” instead of “to”? When I posted this poll on LinkedIn, I expected the answer to be “no.” However, I did some research and was surprised by the results.

Go with “to” most of the time

Generally, it’s better to write “to” than “in order to.”

Shorter sentences are typically easier to understand. That’s why I’ve devoted many words to suggesting how you can make your writing more concise. In fact, that’s a focus of my investment commentary webinar. I’ve given many examples of how to shorten your writing in “Word and phrase substitutions for economical writers.”

As the Doris & Bertie website says: “‘In order to’ isn’t more precise. It doesn’t provide any extra meaning – just extra wordage for your reader to trawl through to get to the important words in the sentence.”

However, there are exceptions to the rule of shorter is better.

Clarity may require “in order to”

In rare cases, “in order to” must be used for clarity. Here’s an example I found in Amy Einsohn’s The Copyeditor’s Handbook:

CLEAR: “Congress modified the administration’s proposal in order to exempt small businesses.”

UNCLEAR: “Congress modified the administration’s proposal to exempt small businesses.”

In the first sentence, it’s clear that Congress acted to exempt small businesses. The second sentence could mean that. Or, it could mean that the administration wanted to exempt small businesses and Congress acted against that.

Rhythm may benefit from “in order to”

Sometimes a sentence just sounds better with the addition of “in order to.” In response to my LinkedIn poll, Paul Bobnak gave me this example from the preamble to the U.S. constitution:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

What will YOU do?

Will you adjust your use of “in order to” after reading this post?

I will continue to ruthlessly trim most instances of “in order to” from my clients’ writing, and I will sometimes leave them in place.

Disclosure: If you click on an Amazon link in this post and then buy something, I will receive a small commission. I provide links to books only when I believe they have value for my readers.