Improve your financial writing with these rules

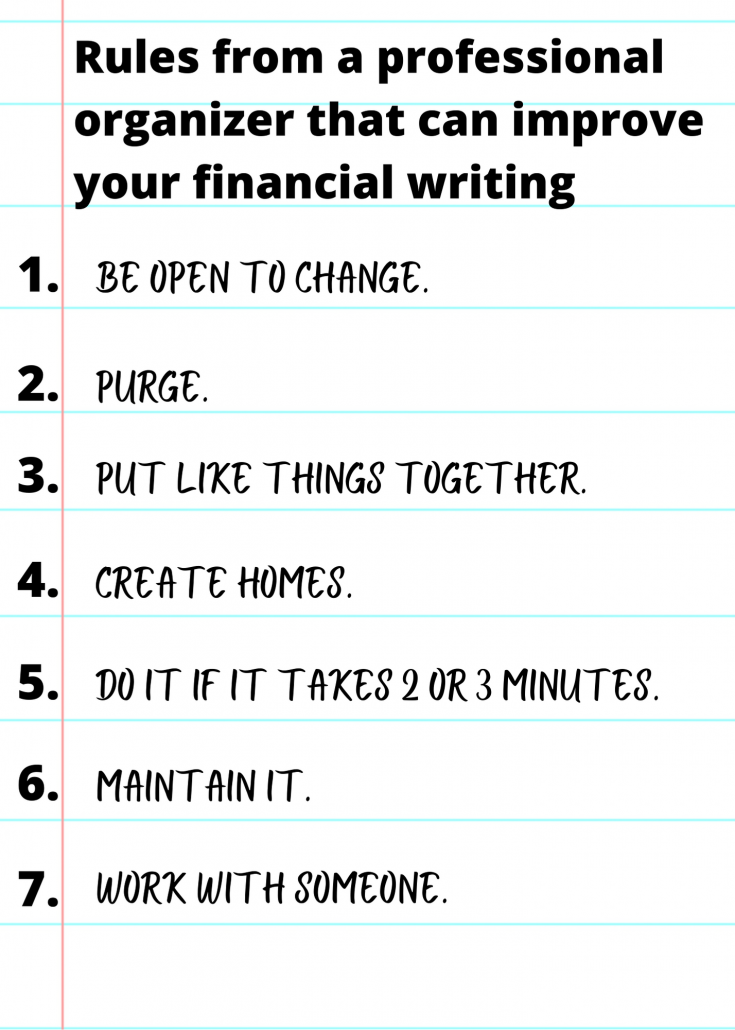

Sometimes I find inspiration for my writing in unusual places. Most recently, it appeared in a newsletter from a professional organizer. Lorena Prime’s “7 Golden Rules of Organizing” made me think about how you can improve your financial writing skills.

Rule 1. Be open to change

It’s not easy to change your financial writing style after putting your words together in the same way for many years.

However, the rules that you learned in school may no longer apply. For example, I learned in typing class to put two spaces after every period. Today, one space is the standard practice, as explained in Farhad Manjoo’s “Space Invaders: Why you should never, ever use two spaces after a period.” Similarly, today a much more personal, casual style of writing prevails than when I entered the business world. For example, when I rewrote my website in 2015, I changed my biography from using “Susan Weiner” to “I.”

Also, there are always new areas where you can learn things. I try to take at least one writing-related class every year. I also read extensively and ask questions of the experts around me.

You’re a smart person who can learn. Take advantage of your curiosity and intelligence to try new approaches to your financial writing.

Rule 2. Purge

One of the biggest curses of financial writing is wordiness. Purge those excess words from your writing.

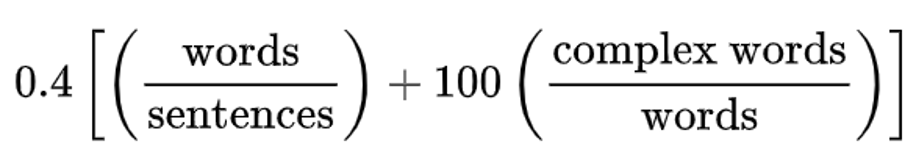

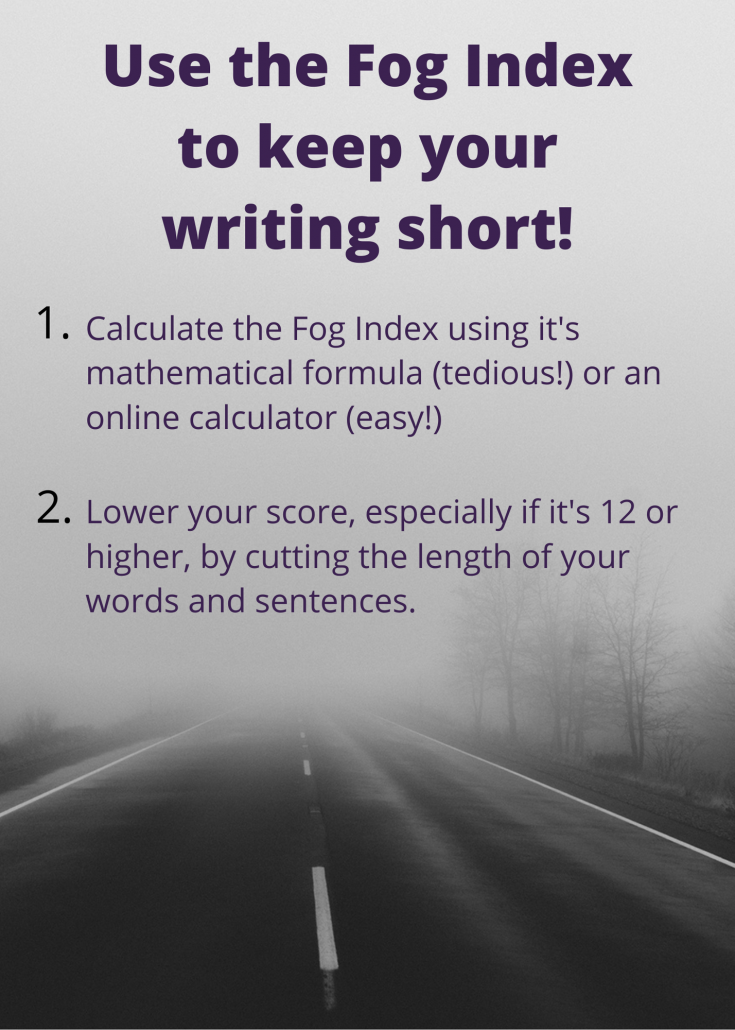

While you’re at it, replace multisyllabic jargon with simpler words that count as plain English. I mentioned one tool for identifying text that needs purging in my post on “Donald Trump, grade level, and your financial writing.”

Rule 3. Put like things together

Keep like with like, as I keep my sweaters together in one drawer

Financial writing that’s well organized is easier to read than writing that hops from one topic to another and then goes back and forth again.

Divide whatever you write—especially longer pieces, such as white papers or quarterly letters—into distinct sections that each discuss one topic.

I describe an example of how to do this in “Key lesson for investment commentary writers from my professional organizer.”

Not sure if you’ve succeeded in putting like things together? You can outline or diagram the topics covered in each paragraph to check. The color coding used in Roy Peter Clark’s margin analysis technique may help.

Rule 4. Create homes

Your ideas for articles, blog posts, and longer pieces deserve homes. Creating a place where you store your ideas (and the data to support them) will help you to find them when you need them. There’s nothing worse than sitting down at your keyboard with no idea of what you want to write about.

You can house your ideas in a way that suits your style. Some people write notes by hand and cram paper copies of relevant articles into manila folders. Others have embraced virtual repositories, such as word-processing documents, Evernote folders, or online mind maps. I store my blog post ideas as Microsoft Outlook tasks.

Rule 5. Do it if it takes 2 or 3 minutes

I’m stretching to apply this rule to your financial writing. However, I’d like you take advantage of even small time slots to work on your writing.

For example, if you’re struggling to write a blog post, commit to spending 15 minutes on it. What you write doesn’t have to be great. It’ll get your mind thinking. You may develop momentum and keep going after your 15 minutes end. Even if you stop after 15 minutes, the ideas will continue marinating in your head.

Only have two or three minutes? Brainstorm ideas for future topics. Try my Barbie-inspired technique if you’re out of ideas.

Rule 6. Maintain it

You must write to improve your financial writing skills. Write regularly—daily, if possible.

Rule 7. Work with someone

I’m a big believer in classes—and getting feedback from others—as a way to improve one’s writer. Even non-financial writing classes can make you more aware of your writing’s strengths and areas where you need to improve. I took many writing classes through adult education programs while I was learning to write better. None of the classes had anything to do with investments or other financial topics.

If you’d like to focus on financial writing, I offer coaching and my financial blogging class, “How to Write Blog Posts People Will Read: A 5-Week Writing Class for Financial Advisors.” I also lead writing workshops on email and investment commentary for professional societies and corporate clients.

How are YOU working to improve your financial writing?

I’m always interested in learning from you. Tell me how you’re improving your financial writing.

By the way, if you need a professional organizer to help you get your office in shape, I recommend Lorena Prime, whose article sparked this post. She is a woman of many talents. She has also acted as facilitator for my annual investment commentary webinar.

Paper image courtesy of adamr/FreeDigitalPhotos.net